Image source, Getty Images

-

- Author, Writing

- Author’s title, BBC News World

Its creators say that the Vera Rubin Observatory “will mark the beginning of a new era in astronomy and astrophysics.” Maybe that’s why he is named: she did the same as scientific.

Rubin (1928-2016) was an American astronomer whose pioneer work contributed the first convincing evidence of the existence of dark matter, one of the greatest mysteries of current astrophysics.

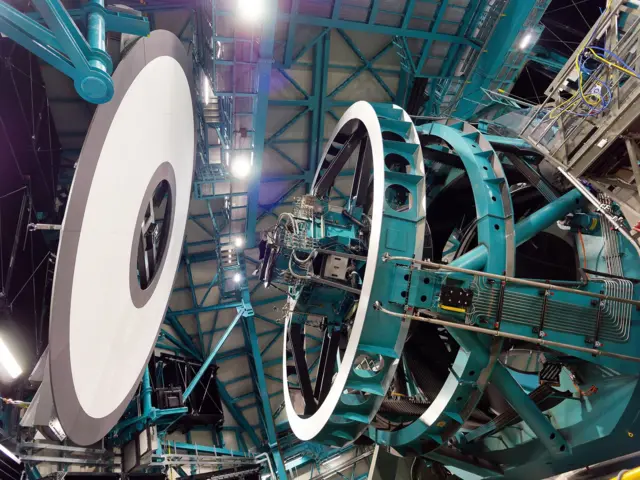

This Monday the first images of the observatory baptized in his honor will be revealed and which has the largest and most sensitive digital camera in the world.

Located at the top of Cerro Pachón, in the Coquimbo region, in Chile, this Astronomy Center will first study real time explosions, in addition to supermassive black holes, variable stars, asteroids, comets and more.

All this thanks to your sensor with 3,200 megapixels.

“Hundreds of ultra high definition television screens would be needed to show a single image taken by this camera,” reports the observatory that belongs to the National Foundation of Sciences and both the US Department of Energy.

And he adds: “With the information that Rubin will provide, we can better understand the universe, the chronicle of its evolution, immersing ourselves in the mysteries of energy and dark matter, and having the answers to questions that we still do not even imagine.”

Image source, RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/DOE/NSF/AURA/B. Quint

A star between stars

Being a girl, Rubin built her first telescope with a cardboard tube and small lenses she bought in a scientific material store.

Her love for astronomy had the support of her father, who even took her to amateur astronomers meetings, according to the profile of the US Natural History Museum.

Although his family always encouraged his talent and passion for science, when Rubin told his physics professor at the Institute – where he was practically the only girl – who planned to go to university, he recommended that he avoid scientific careers.

She ignored her and became the only astronomy specialist who graduated from the prestigious Women’s University Vassar in 1948.

When he sought to enroll as a graduate student in Princeton, they were told that women were not allowed to enter the university’s postgraduate astronomy program, a policy that was not abolished until 1975.

Then he appeared at the University of Cornell, where he studied Physics. Then he went to the University of Georgetown, where he obtained his doctorate in 1954.

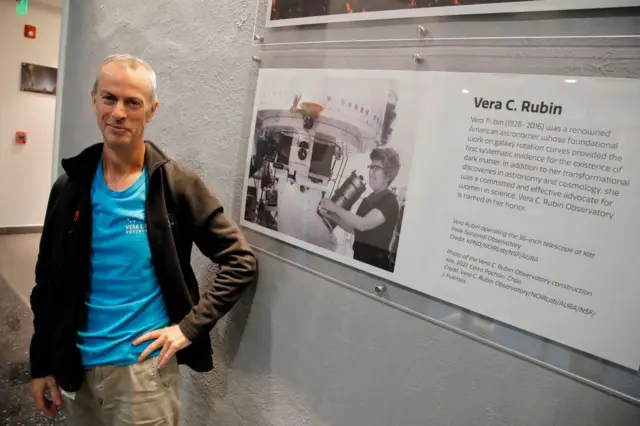

Image source, Rubinobs/noirlab/slac/doe/nsf/aura/w. O’Mullane

In the 70s, Rubin and his colleague Kent Ford studied more than 60 galaxies and discovered that the stars of the outer edges moved with the same speed as those of the center, something that did not obey the laws of physics.

To reconcile their observations with the law of gravity, the scientists proposed that there were matter that we cannot see and called it dark matter.

At first many astronomers were reluctant to this idea, “but the observations were so unequivocal and the interpretation so simple that they soon realized that Rubin was right,” explains the US Natural History Museum.

Now the Vera Rubin Observatory has as one of its objectives just understand the nature of dark matter.

“We have never been able to directly see one of these particles of dark matter, although they constitute more than 80% of all the subject of the universe,” says the observatory.

“What we can see,” he continues, “is the gravitational effect that dark matter has on galaxies and their distribution in the universe.”

In this sense, the Observatory will have as one of its tasks catalog more than 10 billion galaxies to understand how many there are a certain size.

“If we see a lot of small galaxies, that would support our current current hypothesis on the properties of dark matter,” explains the observatory.

Image source, Getty Images

Its place and that of others

During almost his entire Rubin career he had to face the prejudices of those who considered that the life of a mother of four children was incompatible with science.

But she was always combative.

An example occurred when he could finally have access to the Palomar Observatory, where there was no bath for women, a problem that solved a paper skirt at the door of the men’s bathroom.

According to the biography VERA RUBIN: A LIFEpublished in 2021 by Jacqueline and Simon Mitton, its impact “was not limited to their contributions to scientific knowledge, but also helped transform scientific practice, promoting the career of women investigatives.”

He fought for the inclusion of women in scientific committees and conferences, for hiring more teachers and rewarding female colleagues.

His studies earned him numerous honors, including being the second woman astronomer chosen for the National Academy of Sciences of the United States. But there are those who believe that the acknowledgments in life were not up to their career.

“Despite being one of the most influential astronomers of his time and the revolutionary of his discoveries, Vera Rubin was not awarded with the Nobel or received in life the same recognition as some of his companions,” he says in his biography.

He is now being recognized posthumously with the first American observatory that bears the name of a woman.

Subscribe here to our new Newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and act.